In 1987, three Black men from the South Side of Chicago created the first of two self-published ‘zines documenting Black underground art, history, and life. Think Ink, the brainchild of Robert T. Ford, Trenton Adkins, and Lawrence (Larry) Warren, was a large 10.5’’ by 16’’ magazine similar in format to Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine.

According to a September 1993 Owen Keehnen interview published in Outlines newspaper, Ford, the publisher, and editor stated that Think Ink was: “… very Black and not very gay …” A bold three-thousand copies of Volume One, Issue “O” was printed, initiating its Nov. 14, 1987, release. And a celebration was held at Wholesome Roc Gallery & Cafe to a full house.

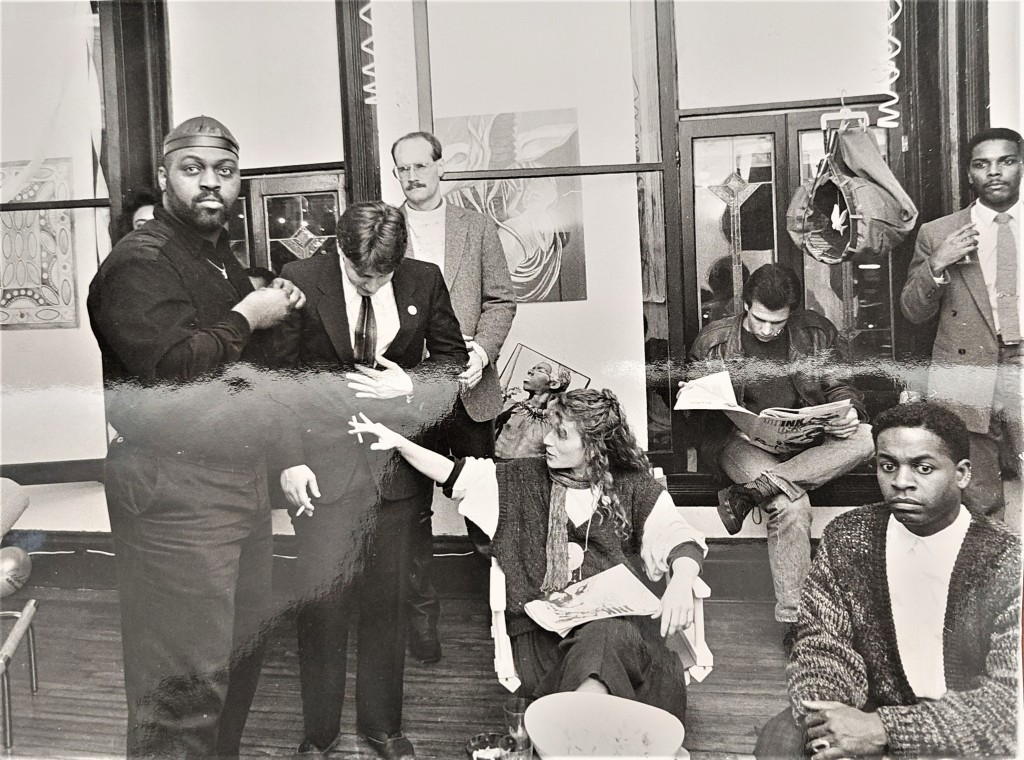

Wholesome Roc Gallery & Cafe, 1987

I appeared on the cover in a satirical homage to Roots, the Alex Haley miniseries depicting the brutality of slavery, starring Levar Burton as Kunta Kinte, that captivated the nation in 1977. Adkins did the styling, and Paul Mainor of Mainor-Martin photography captured the now-iconic image.

The second issue, published in the spring of 1988, Volume One, Issue “1,” featured local model Aisha Mays on the cover shot by the late fashion photographer Ernest Collins. Adkins did the makeup, and I did sleek hair in a nod to Harlem’s 1920s Jazz Age, which was hot back then. Writing for Artforum in 2018, art historian Solveig Nelson declared it “evokes both the Jazz Age and voguing scene of the ’80s, characteristically bringing together different instances of cutting-edge glamor in African American culture.”

Spring Issue “1” (1988) photographed by the late Ernest Collins

Although it was the trio’s first experiment in publishing, with Adkins and Warren serving as co-editors, Think Ink ceased publishing after two issues due to a lack of funding. Nevertheless, its impact was far-reaching, featuring interviews with Dr. Margaret Burroughs, founder of the DuSable Museum of African American History; DJ and music producer Frankie Knuckles; fashion designer Isiah and more. All fused together with art, poetry, fashion, music reviews, and Adkins’ “TEE” gossip column in a way never before seen in the Black community.

Nelson says Think Ink’s voice was “… loud & varied embracing cultures and countercultures of thinkers male/female/black/white/straight/gay/etc.” And independent culture and fashion magazine Document Journal writer DeForrest Brown Jr. refers to it as a “post-soul aesthetic” stemming from the Black Power and Black Arts Movements.

(Illustration by Michael Asendio, NYC ©2022)

Short-lived, yet ahead of its time, the experience yielded “good information,” as Warren would put it years later. The lessons learned were priceless and prepared them for their subsequent publication focusing exclusively on the underground Black gay community, thus catapulting their names into the annals of history.

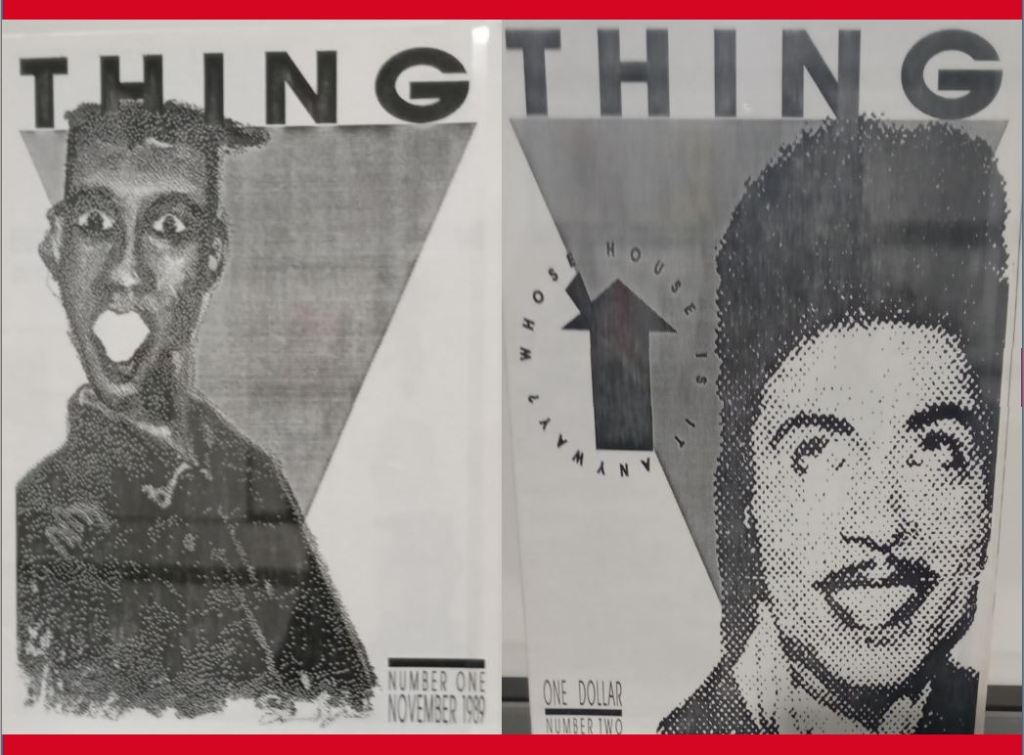

THING Mega ’Zine

Unlike its predecessor, Think Ink, THING magazine was much smaller (8.5’’ by 5.5’’). But what it lacked in size, it made up for it with provocative editorial content. THING was bold, trend-setting, and unapologetically Black, yet it was never meant to be subversive. “We wanted to make a magazine that would be a way of documenting our existence and contribution to society. Our idea was not so much to radicalize or subvert the idea of magazines as to make one from our point of view. It wasn’t about deconstructing what a magazine is, it was playing within its perimeters.” Ford shared with Keehnen.

The fact that all three men were openly gay is coincidental, but it served its purpose by heightening THING’S editorial content appealing to the sensibilities of both the Black and white gay communities in Chicago. This time around, distribution for the first two issues was targeted and much smaller than Think Ink. “It was cautious optimism,” Warren characterized it, “from previous experiences.”

On the cover of issue No. 1 – published November 1989 – an oil pastel painting of me by fine arts artist Simone Bouyer was chosen. The Living Flame and King of Rock and Roll, Little Richard, appears on issue No. 2. Only a couple hundred of each issue were published, but what happened next surprised everyone. THING caught on like wildfire, and by issue No. 3, distribution was expanded nationwide from New York to San Francisco. Chicago native Anthony Jackson was stationed at Alameda, CA, and remembers walking into a Black gay bar in Oakland, CA. “I went in there, and they had all these different magazines. (There’s) THING and all these other magazines like from Europe,” he stated.

Subscriptions increased as word spread of THING’S racy interviews with rising stars like NY drag queens RuPaul, Lypsinka, and Lady Bunny (THING magazine Issue No. 6). And there was Chicago’s very own drag star Joan Jett Blakk who ran for mayor and eventually for U.S. president. Interviews with artists like early AIDS activist Essex Hemphill, music producer Bill Coleman, and film producer Marlon Riggs testify to THING’S penchant for spotting emerging Black talent and providing a platform to be seen, heard, and taken seriously.

With a stroke of luck – the right mix of editorial interviews, commentary, Adkins’ gossip column, music playlists, opinion pieces, film reviews, short stories, and timing – the trio had finally achieved the success they envisioned. And THING magazine began to fulfill a deep void in the Black gay community and beyond.

As popularity spread, the ‘zine increased content, with each succeeding issue attracting a wider pool of contributors, writers, and volunteers. Editorial content became slicker as THING carved out its niche, becoming the premier go-to source for information within the Black gay community. After four years, THING surged from twenty-six pages to forty-six pages. But success came with a price.

According to Ford, THING had reached “an odd scale” and was “too small to generate lots of funding and too large to run without a staff,” he shared with Keehnen.

Meanwhile, by issue four, Adkins noticed editorial content starting to veer off-point. He sent a letter to staffers expressing concerns about their well-being, acknowledging that everyone was under some “stress” due to HIV/AIDS directly or indirectly. Adkins admonished everyone to “… be kind and understanding to each other.”

Success and circulation continued to accrue, but Ford was ready to call it quits after four years for several reasons; chief among them was his health. Ford was battling opportunistic infections because of AIDS and was hanging in there on a “day-to-day level,” he told Keehnen. “Thing had reached a point where it was creating more stress in my life.”

The final THING magazine No. 10 was published in the summer of 1993 with Jazzmun, the living Black Barbie, on the cover. More than a year later, Robert T. Ford passed away on October 2, 1994, surrounded by family and a few friends. Adkins passed away in 2007 due to similar health reasons. And Larry Warren passed away in December 2016 from diabetic-related complications.

Despite the trio’s early demise, they continued to “work it” from the ancestral realm setting the stage for a fait accompli yet to come. The seeds had been planted, setting in motion a chain reaction. It might have taken 35 years, but things were just getting started.

The Legacy Continues

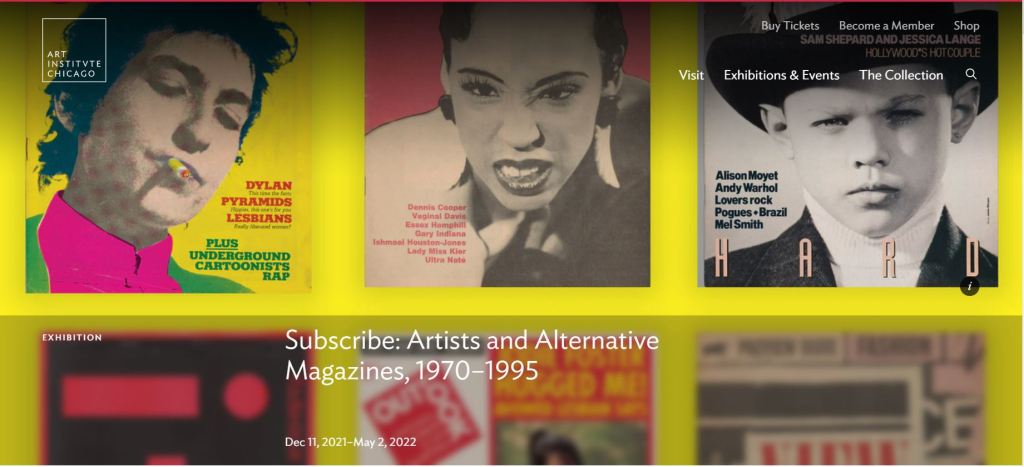

By the time the University of Chicago Ph.D. Candidate Solveig Nelson contacted me on Facebook in December 2017, she was already several years deep into researching the history of Think Ink and THING magazines. Four years later, on December 11, 2021 – during the height of the Omicron variant – Subscribe: Artists and Alternative Magazines photo exhibition opened to the general public with proof of vaccination requirements and without much fanfare.

But no one could’ve predicted what happened next: “It’s the most popular photo show in the museum’s history,” says the art historian candidly. Nearly a decade of relentless pursuit had finally paid off!

The exhibition took an unfiltered look at various underground magazines that circulated from 1970-1995, influencing pop culture on both sides of the Atlantic. Artistic publications from Chicago, LA, London, and New York gave platforms to a host of underground contemporaries that spoke to the issues of their day while giving you a glimpse of things to come.

Drawn to the complex subtleties, the overtness, and sometimes quirky irreverence, Nelson states, “I was surprised in this [Think Ink] article how bravely she talked about capitalism,” referring to Dr. Margaret Burroughs, founder of the DuSable Museum of African American History, “… it’s a really radical interview. And then, in the same pages, you talk to Frankie Knuckles. And that combination of cultural figures, I just don’t see it anywhere else in any publication.”

Drawing on their multi-disciplined backgrounds, the founders tapped into the power of storytelling, building on the legacy of the Black Arts Movement while crafting a new voice for Black gay men in print before the rise of the internet.

Nelson recalls meeting Adkins through Michael Thompson, Robert Ford’s former lover, in 1998. “Michael had the habit of inviting people over without saying who else he had invited over. Trent, Michael, Sadie Benning, and I all intersected at Michael’s North avenue apartment one afternoon. It was special,” she shared in an email. “We watched a video together and talked for hours … I know that we talked about experimental art and how it was too often gendered as male. Trent was brilliant as a conversationalist and as a thinker. He had such a range of expertise. He proudly told me about Thing magazine. He had so much love when he discussed this project.”

The chance encounter with the ever charismatic Adkins left an indelible impression influencing her decades later as a Visiting Curator at the Art Institute of Chicago and co-curator of the Subscribe photo exhibition. “I think the reason this acquisition means so much to me… things are valued after people die, and you know then people are like, this is valuable … this actually changed culture. This had a big effect,” she commented during the exhibit.

Ultimately, THING served as a beacon of hope for the underground arts community and beyond, establishing a new narrative for how Black artists perceived themselves and the world around them. Black gay women and men were coming of age in Chicago and celebrating their accomplishments, whether it was education, working a job to provide for their family, pursuing careers, starting a business, or being married to the Music Box or Warehouse dance floors on the weekends. They had something to offer; they knew it and were unapologetic about it.

The timing of the renewed interest in Think Ink and THING is almost prophetic against the backdrop of current events. Today’s headlines could easily be interchanged with those from 35 years ago as monkeypox, reproductive and transgender rights take center stage. Back then, it was HIV/AIDS and Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Jewish civil rights activists fighting against police brutality – Rodney King, the Republican Christian Right, and the Moral Majority. And true to form, as George Bernard Shaw mentions in the “Revolutionist’s Handbook,” the more things change, the more they stay the same.

By its tenth issue, THING reached a circulation of roughly 3K subscribers worldwide – a “gigantic” feat, according to Keehnen. And that is a huge accomplishment for an underground ‘zine.

THING welcomed intersectional collaborators of all sorts with open arms who believed they had something to contribute to society. All the while establishing a template for future generations of content creators to control their stories, fashion their brands, and build on the rich legacies that preceded them.

The interest in our work as part of the collective team is an honor and humbling as the House of Thing (Simone Bouyer, Stephanie Coleman, and I) seek to share our stories and lessons learned with today’s pioneering artists while connecting with the legacy builders before us.

Together, we aim to continue the uncompromising and powerful tradition of African storytelling, building on the vision begun by Robert T. Ford, Trent Adkins, and Lawrence (Larry) Warren. And who knows what might happen next? Anyone or anything can become the next hot thing. As Ford once said, “… Someone can be famous because THING thinks they’re famous.”

THING: She knows who she is